A 20th century architectural account of Charlton Park prepared for Cheltenham Civic Society recorded that under the house's 18th century brick shell is a timber-framed 'Tudor' building with "fine oak beams", and from the view looking down on the roof, it is clear that at each end of the entrance front there was, in bygone centuries, a portion (heightened in more modern times) between the two ends. These gabled parts formed the ends of two wings which extended towards the lake. What the wings with the entrance front did was to enclose a courtyard open to the sky, with windows looking onto the courtyard. Some of the latter still exist. They are stone mullioned and apparently of Stuart (1603-1714) period. They no longer look on to a courtyard but on to the walls of an oval building which has since been built in the courtyard and rises up about two-thirds of the height of the main building as it is today. There is some very old, nicely moulded colour-washed oak panelling in a top room, unlike the other panelling, believed to be contemporary with the Stuart windows.

This ghost of the timber-framed medieval house was given the brick skin we see today by John Prinn the elder. The cost of the bricks used in 1713-14 confirms that this was a major undertaking. Two bricklayers were employed; John Pope was engaged to make the better brick, finding local clay, fuel and labour. His bricks cost 7s 4d (36p) per 1000. John Dobs, using clay from Prinn's own land, made 80,000 bricks at 6s 2d per 1000 and it is assumed the better bricks were for the outside and the cheaper ones for the inside work and that Prinn, beside single brick party walls, was erecting a double brick wall outside the old timber frame. He needed this to support the heavy stone roof. If he only covered the front (40ft), two sides of the north wing (another 20 + 16ft) and the end of the courtyard (24ft), taking brickwork to the height of the house (about 30ft) he had to build some 104 linear feet. If the bricks were comparable in size to those still visible on the south front of the house, he needed twice 30 bricks per square foot. Dobs supplied 80,000 and Pope approximately the same. Prinn's steady improvement plan continued with the building of the west block and repairing the front and north end of the house with brick in 1717, all undertaken without wasting money on unnecessary ornamentation.

The clay used by Dobs for the bricks almost certainly came from a large hole excavated against Old Bath Road, on the land afterwards called Clay Pit Ground. The water filled pits appear on the 1811 map and next to the Old Bath Road Toll Gate on the 1843 map. The pits were later filled in but a builder who erected houses on Old Bath Road early in the 20th century recalled that he encountered trouble there because by then no one remembered the pits.

The 'pine end' or 'pin end' of the new Home Farm barn had taken 3864 bricks. John Pope supplied 5200 for work on the barn and stables in 1711 and it is these figures from Prinn's account book that offer some means of estimating the work done 1713-1714. Whilst Prinn was fastidious about certain work and the materials used to bring his property up to date, his account book suggests a pig-in-a-poke type deal after the purchase of a second-hand cider press that lasted only 10 years.

Most of the roofing slates were supplied by Mills of Bidford-on-Avon, Warwickshire in 1711, coming by river to Tewkesbury, and then by wagon to Charlton Park. The 43,000 slates cost him £9 13s 6d.

The Prinn family's improvements included diverting the ancient 'Hollow Lane' (the public road that separated Home Farm from the house) and building a new barn and stable c1711. Besides the re-fronting of the old house with a brick façade, other work by John Prinn included adding additional wings resulting in the asymmetrical front shown in Robins' painting. Prinn's son (also John) continued to develop and improve the estate after his father's death. In 1736 he bought a quantity of bricks from Herefordshire, the clay making these bricks a distinctly brighter red than the clay quarried on the Forden estate for the earlier ones. In Robins' painting the extensive brick walling is shown in a much deeper red than the brick in the earlier north block of the house. The roof may have changed from thatch to stone after 1701 to reduce the fire risk and take advantage of readily obtainable Cotswold tiles. The west facing pediment and cornice were added some time after the 1740s because they do not feature in Robins' painting, but are present in the 1789 engraving.

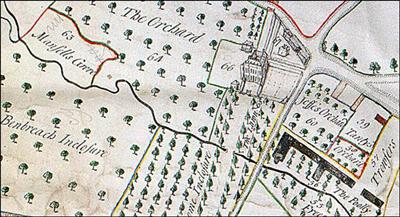

By the 1740s the much smartened-up Forden House looked out across gently sloping parkland with man-made lakes and canals towards Leckhampton Hill. It had a large walled kitchen garden, knot garden, flower gardens, lawns and gazebo, bowling green, extensive orchards, meadow, dovecote, coach house, stabling, barn, granary, rick-yard, cottage and sundry outbuildings and employed sufficient in-house and estate staff to maintain it all. From what is still around us today and from earlier maps we know the various owners also had serious arboreal ambitions, setting out avenues and other serried plantations of trees, both indigenous and foreign. Amongst other species there were oaks, elms, sycamores, ilexes, cedars of Lebanon, Spanish chestnuts, Scotch firs and Wellingtonia (giant sequoia, from California).

© Glos ArchivesClifford's 1746 birds-eye perspective showing the Mansion, Home Farm, ornamental lakes and plantations.

© Glos ArchivesClifford's 1746 birds-eye perspective showing the Mansion, Home Farm, ornamental lakes and plantations.