Dodington Hunt (Prinn) changed the mansion's name from Forden to the more impressive Charlton Park c1784, during the period of his own major alterations to the house and park (between 1782 and 1796). This is when he inserted a drawing room into the courtyard for himself and his wife, Elizabeth Prinn. He remodelled the west front and added the attic storey and pediment not present in Robins' c1740 painting. Notes in his rent book beginning in 1784 include: 'My great object at first was to turn the road between the Garden and the House and to buy the property in Benbreach. With respect to the first I found no opposition and I had the new Road established by two Justices, Messrs De la Bere and Wynyatt in beginning of July 1784, the making of which cost about £10 including the new Fence. In the autumn of 1784 built my Icehouse £20. In October of the same year began throwing down the Banks and making the Piece of Water, Lawn before the House, sunk Fences, Gravel Walks etc, which I hope will be completed with the Bridge within side of the Park in the next spring as near as I can estimate about £600'. [This reference to 'throwing down the banks' and 'making the piece of water' probably refer to the sculpting of the 'amphitheatre' where the pond and icehouse were located]. With respect to Benbreach [the area covering what is now Reeves Field & Cox's Meadow] in the summer of 1784 began my new Garden which with conservatory and Hothouse finished about May the following year cost me about £950. '1785 all the lands in that field ploughed this winter and levelled to be sown to turnips in summer of 1786 and barley and seeds in the spring of 1787. 'In the spring of 1787 I got two Justices to stop the Sandy Road from Home Farm gate to the bottom of Benbreach. In the spring and summer of 1788 moved the pales and made the new work round the new Park, made the fences and plantations.....sowed the old Sandy Road to barley and seeds.........1796 made the fence new by the Pale in the New Park against the Bath Road' [these changes almost certainly explain why the Eagle Gates were moved from Sandy Road and nearer to the house].

From these notes we may safely deduce that in addition to the water-gardens of the previous century, this was the next period in which fashion took over from function, as former field and meadowland was enparked and stocked with deer. Having achieved all this (some 60 years before the first photographic studio came to Cheltenham in 1841) Doddington Hunt understandably wanted to record Charlton Park and an artist was commissioned. The location of the original painting is unknown but the 1789 engraving shown on page 15 almost certainly comes from it. Whether the completion of this programme of work was coincidental with King George IIIs five-week stay in Cheltenham in 1788 is also unknown, but during this regal excursion to the Cotswolds the King visited Charlton Park, once again reinforcing the significance of this ancient seat.

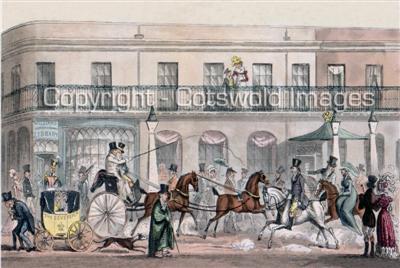

In the afterglow of such an important visit and the royal seal of approval it bestowed on the town, countless others seem to have spurred their horses towards Cheltenham to quaff its waters, wishing to be seen in equally good company as themselves, and sustaining the kind of savoir vivre Cheltenham Spa became synonymous with for another century or two, during which a few of its visitors were no doubt ably hosted in the luxuriant tranquility of nearby Charlton Park. After 1790 newer Georgian and Regency parks and leisure areas began springing up after more subterranean aquifers were tapped and quaffed by an increasing number of folk choosing to visit or settle in the rapidly growing spa town. Certain social affectations accompanied the 'taking of the waters' and these attracted social and satirical commentary in publications such as 'Spy', renowned for poking gentle fun at the antics of English society. Faddish or otherwise, such imbibing increased after King George III visited the town in 1788 with Queen Charlotte and three (Princess) daughters of their 15 children.

After William Cobbett rode through the High Street in 1826, his tongue-in-cheek commentary of Cheltenham's upper-class residents and visitors included the following:

'The lame and lazy, the gourmandizing and guzzling, the bilious and nervous'.

© Cotswold Images

© Cotswold Images

Regency class-satire: 'Eccentrics in Cheltenham High Street' by Robert Cruikshank, 1824.

It appears a variety of favourable circumstances, including the 1788 royal visit, the perceived efficacious quality of the waters, the geographical attractiveness of the area, the availability of building land and the emerging social scene, all combined to attract an increasing number of prosperous and notable folk to Cheltenham. More and more fine houses, representing the peak of Georgian architectural elegance, driven by wealthy residents and ambitious planners resulted in new leisure parks, roads, squares, avenues, crescents and England's finest inland promenade, accompanied by a simultaneous expansion (and collapse) of all manner of supportive trades and professions, as the rewards of boom and scars of bust left their inevitable trail. Whether we accept that this great influx of gentry and other worthies headed for Cheltenham on the back of a royal visit or the reputation of its dubious brine is another matter, but the town positively expanded amongst the usual fits, starts and cyclical property booms of the 18th and 19th centuries. It continued to neatly modify itself during the Victorian and Edwardian periods, most of it kept intact for us to enjoy today, and throughout all this, Charlton Park sat quietly in the wings, the noble matriarch of so much future housing that was still to arrive on her own 20th century doorstep.