A major turning point appears to have been reached around 1960, with land-hungry developers baying at the heels of the current owners of this historic hunting ground. This was also when, under the Gloucestershire County Development Plan's First Five-Year Review, Charlton Park was likely to be allocated (zoned) as 'private open space'. The College Council felt that this proposal would result in inadequate use being made of the land and lodged a formal objection. The objection was heard before an Inspector of the Ministry of Housing and Local Government in February 1961, as a result of which the Planning Authority entered into a formal agreement with the College, with the approval of the Inspector, that they would be prepared to recommend proposals for residential development of the park, subject to the following conditions,

- the land shall for the most part retain its park-like character

- a landscape plan for the whole area shall be prepared which preserves as many of the trees as possible

- building and layout shall be of a high standard of design and landscaping and the development shall be of open character, mainly in the form of blocks of flats including possibly some high blocks. [without actually specifying how high].

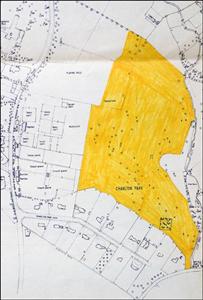

© Cheltenham CollegeCheltenham College's proposed development area c1960, included part of Reeves Field

© Cheltenham CollegeCheltenham College's proposed development area c1960, included part of Reeves Field

© Cheltenham College1960 plan of the proposed development area incorporating Lower Reeves Field (top left)

© Cheltenham College1960 plan of the proposed development area incorporating Lower Reeves Field (top left)

As owners of the land in Charlton Park Cheltenham College naturally sought to maximize control of and return from their intended development within it. With external developers also knocking at the door, the College was well aware of the commercial potential of what they owned here, which was effectively a quietly grazing, thirty year old cash-cow, ready to be taken to market where it would generate urgently needed improvement and modernization income for the College in the process. In 1960 it was considered that the value of the land for residential development was something in the region of £100,000, providing that access from Old Bath Road could be agreed.

After the formal planning agreement was signed in 1961 the College consulted their London architects - Louis de Soissons & Partners. This firm had already undertaken other College modernization projects, including the conversion of the former Chapel into a theatre, laboratory upgrades, and, following the acquisition of Thirlstaine House in 1948 (former home of Lord Northwick) its conversion to meet a growing demand for additional buildings. To help finance future College expansion and refurbishment plans, Louis de Soissons were instructed to draw up outline development plans for Charlton Park. Plans were duly prepared and statutory permissions sought to convert some 26½ acres of parkland, including Lower Reeves Field, into a residential development.

Being an Educational Charity, Cheltenham College (the owners) were charity trustees and as such obliged to satisfy the Secretary of State for Education and Science they had taken due steps to obtain best-price for their 26½ acres. Now influencing such plans was the aptly named 'brutalist' socially progressive design movement that flourished in the 1960s. The combined result saw the low-rise, high-quality exclusive type housing favored by Reeves brushed aside as 'modern' reach-for-the-sky schemes rolled off city drawing boards, which, in a city context were almost tolerable. Proposing such concrete structures here, in the heart of the Cotswolds, particularly within the historic confines of Charlton Park would doubtless have caused Reeves to turn in his eight year old grave. Whether the plans were driven by the College Council or the London architects is now unknown. Looked at another way, through the eyes of a long departed artist, whose bones may have rotated in similar fashion had it all become set in concrete, Robins may well have found it easier to paint his characteristic bird's-eye perspective from some vertiginous penthouse in the sky, but the tranquil parkland scene below him would unquestionably have been a giant blot on the landscape - despite the lovely backdrop. In recent times, an influential countryman living in Gloucestershire, commenting on just one similar structure dominating Birmingham's skyline, disapprovingly called it, 'a designed accident'. It is reasonable to assume that Prince Charles may have considered five similar structures here in Cheltenham to have been something of a designed multiple-accident!

On Reeves' death in 1952, the covenants protecting Charlton Park were transferred to the College and their protection effectively evaporated, leaving the College able to enforce them, but unfettered by them. This did not bode well for this historic parkland, as its future development style lurched to the other extreme. Reeves' legacy of trees, park and pastureland now lay exposed upon drawing boards of London architects, the fruits of which were intended to pour into yawning bursarial coffers. Ironically, what a London lawyer had bought and sought to preserve here in Cheltenham during his lifetime and beyond, was about to be swept away root and branch by London sophisticates, looked down upon if you like, as was so much else in this traditionally low-rise Regency Spa Town. The likes of Cobbett and Cruikshank would have had a field-day, with comments and caricatures to match the impending disaster-style panorama that, no thanks to Cheltenham College, came perilously close to scarring the town's attractive outline; one that had been appreciatively viewed from nearby hilltops during recent centuries and would have been deplored in similar fashion in the one to follow.