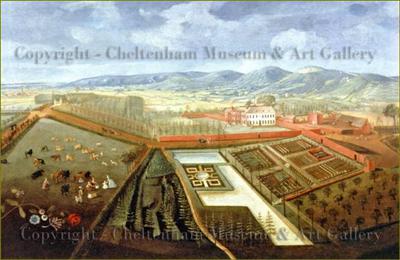

By the mid-18th century, during the family Prinn's three-century tenure, they were sufficiently proud of what they had created in Charlton Park to commission Thomas Robins, a local artist (born Charlton Kings 1716, died Bath 1770) to paint this wondrous vista on canvas. Forden House, in its luxurient tree-lined parkland, with kitchen and water gardens, home farm and Cleeve Hill backdrop are frozen-in-time in this truly magnificent, below-escarpment Cotswold scene. Intentionally or otherwise, Robins chose to marginalise the comparatively insignificant market town of Cheltenham amongst the background detail as he sought to capture the opulence of the park in this somewhat naïve but otherwise impressive (trapezoidal) panoramic view.

© Cheltenham Museum & Art GalleryCharlton Park c1740, by Thomas Robins. The spire of St Mary's Parish Church, Cheltenham is near the upper left edge (better seen when the picture is expanded). The Eagle Gates (upper left side of the park) were on today's Sandy Lane (Old London Road/Sandy Road)and the orange colouration Robins gives to the two carriageways appear to be a reflection of this surface feature.

© Cheltenham Museum & Art GalleryCharlton Park c1740, by Thomas Robins. The spire of St Mary's Parish Church, Cheltenham is near the upper left edge (better seen when the picture is expanded). The Eagle Gates (upper left side of the park) were on today's Sandy Lane (Old London Road/Sandy Road)and the orange colouration Robins gives to the two carriageways appear to be a reflection of this surface feature.

Flora and livestock appear as a somewhat stylized representation of what was in the park.To help his perspective Robins would very likely have climbed Charlton Kings Church Tower.

The water gardens, fed by the Lilleybrook as it flowed through the grounds are shown in Robins painting in great detail, similar to how they appear on the 1746 estate map. A 'close' adjoining the gardens called Pool Hay or Pooley in 1660, suggests there may have been a lake which could be developed without too much trouble or cost. Giles Greville (1640-1692) envisaged his son Giles retaining the house as a family home, even after much of their land had been sold. He may have created the Dutch water gardens c1685 when they became fashionable, though the first surviving reference to them is not until 1732.

© Cotswold ImagesCheltenham High Street and the Plough Hotel c1740. Bell Lane (Winchcombe St) is just beyond the Bell Inn on the right.Skirts no doubt needed raising when using the stepping-stones to cross the street.The spire of St Mary's Parish Church (c12) and the Market House (c17) can be seen in the background. Only the church survives.

© Cotswold ImagesCheltenham High Street and the Plough Hotel c1740. Bell Lane (Winchcombe St) is just beyond the Bell Inn on the right.Skirts no doubt needed raising when using the stepping-stones to cross the street.The spire of St Mary's Parish Church (c12) and the Market House (c17) can be seen in the background. Only the church survives.

This early view of Cheltenham High Street (after an old monochrome photograph of the painting) is shown to demonstrate the contrast between the opulence of nearby Charlton Park in the 1740s and the contemporary rusticity of the town. During this period the old Market Town was still little more than its 'High Street', through which the River Chelt (combined with the Lilley Brook) was as much welcomed to flush away the unmentionables as it was feared in times of heavy rainfall. With the Chelt in flood a search of our time-line (try using Ctrl-F for searches like this) reveals many streets have always been insufficiently 'high' to avoid the kind of inundations that this little river, when swollen, is capable of inflicting upon them (today it is mostly underground, until the system's capacity is overwhelmed). Despite major and costly engineering projects right up to this day, the flow somehow manages to breach the defences and flood low-lying parts of the town - as hinted at in the introduction of this article. Only future-time will tell if the Environment Agency's ongoing engineering works have finally defeated the forces of nature. In the meantime some of Cheltenham's unfortunate residents continue to see their insurance premiums rise in direct proportion to the town's flood-levels.

When the oil was still drying on these two paintings some of the town's other aquatic-attractions, its spa-waters, were enjoying wider acclaim and by 1788 they had achieved national and international prominence, having attracted the Royal Family to the town - and the rest as they say is history. It now appears that the 1788 royal visit was the catalyst that reversed the town's apparent lack of significance, as implied by Thomas Robins' near banishment of it to the corner-detail of his painting. If so, this may be why Charlton Park and its mansion then slipped almost unnoticed from the gaze of town-focused historians - with the exception of people like Mary Paget, Jane Sale and other members of the Charlton Kings Local History Society, who strove to ensure otherwise. At this point it is again worth mentioning the 'time line', where, almost a century later in 1834, certain High Street improvements were underway when trench-digging for the town's first sewers unearthed reminders of the c1740 High Street painting, including the stepping-stones and ancient timbers. Today's High Street conceals similar traces of the past and if you know where to look you can still find buried tram-lines of a century or more ago.